Encounters with conflict and peace

First steps towards stability

Everyone was afraid. Hutus were certain that the Tutsis would take revenge. Traumatised Tutsis saw every Hutu as a potential killer.

Nobody trusted the authorities. Too many police, judges, government officials and local mayors had participated in the genocide. The country urgently needed some stability - people needed to feel a little bit safe again.

In the first steps to restoring basic law and order, tens of thousands of genocide suspects were rounded up and put in prison. It was rough justice: many innocent Hutus were were locked up while thousands of killers remained free in the villages.

The importance of justice

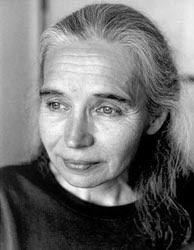

Alison Des Forges from Human Rights Watch said, “Justice is not going to erase the memory of the crimes, but it will provide people with some level of closure. At least they’ll know it has been dealt with, it has been talked about, someone has been held responsible and perhaps even, ideally, the victim has received some form of compensation... It is very important that the truth be known, that the people who were killed be remembered and that their killers be acknowledged.”

Many high level genocide organisers had fled the country. Some began new, comfortable lives in countries such as France, Belgium and Kenya. Survivors watched in disbelief as authorities in those countries turned a blind eye or, in some cases, actively protected these criminals.

Genocide organisers not punished

If you ran into one in Paris, with his fashionable suit and his round glasses, you would say, “Well, there's a very civilised African.” You would not think: “There is a sadist who stockpiled, then distributed two thousand machetes to peasants from his native hill.” So because of this negligence, the killings can begin again, here, or elsewhere.”

from The Survivors Speak, by Jean Hatzfeld

What is justice?

Is it about deciding on a suitable punishment? Is it about what’s fair for everyone? How can you possibly do justice for something as big as genocide?

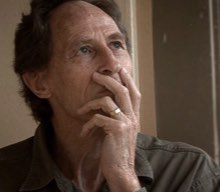

John Steward, a consultant for World Vision, says that he has learnt a lot about justice by watching Rwandans rebuild their country. He believes that, at its most basic, the best justice has two elements.

"The first is where the offender faces what they have done," he says. "I mean that the perpetrator by nature runs away from their victim - they don't want to know them. So the first step of justice is for the offender to stop running away."

The second element of effective justice is where the offender starts thinking in terms of the victim. "They will say something like, 'I'm sorry for what I did and I want to do something for you - I want to repay you in some way for what you have lost'.

"Obviously, Rwandans can't replace life but they also damaged, stole and destroyed property. By replacing some of those physical things and also offering other kinds of support, they can go some way towards restoring everything that was taken away. I don't think justice is ever justice unless that takes place."

Related pages

The aid worker

I CAME TO RWANDAJohn on first impressions. "I saw a country moving at half pace. People full of fear, struggling to get food - frantic to get jobs, dislocated and separated from their communities. I quickly realised that the government was proclaiming the need for justice and the church was preaching forgiveness, but people were hurt inside.... watch

Survivor questions

AFTERMATHJohn on Rwanda after the genocide. “They were tough days. You had this cauldron of a million people who’d lived in exile for up to forty years and two million recent refugees, all coming back to mix with the survivors and with perpetrators who hadn’t yet been identified.... read more

< previous page | next page >

In this section

AN EXPERIMENT IN RECOVERY

Back from the edge

Experiment in recovery

A new Rwanda

JUSTICE

An overloaded system

The importance of justice

Teaching gacaca

Confronting the past

Soft justice?

Has gacaca delivered justice?

PEOPLE WHO KILLED

Helping killers

Sorry

MIND DAMAGE

Recovering from genocide

Living with the pain

Obstacles

Where does it hurt?

BUILDING PEACE

Breaking the cycle

Building peace

Back from the edge

Experiment in recovery

A new Rwanda

JUSTICE

An overloaded system

The importance of justice

Teaching gacaca

Confronting the past

Soft justice?

Has gacaca delivered justice?

PEOPLE WHO KILLED

Helping killers

Sorry

MIND DAMAGE

Recovering from genocide

Living with the pain

Obstacles

Where does it hurt?

BUILDING PEACE

Breaking the cycle

Building peace