Encounters with conflict and peace

The refugee crisis

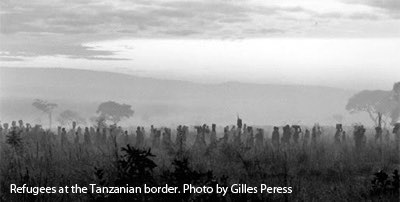

"No one knows the exact number of Hutu who fled Rwanda in the summer of 1994, but the UNHCR after described this as the largest dislocation of a population its aid workers had ever witnessed.

Within a few days after it began, there were seven hundred thousand refugees in Goma and another four hundred thousand at other camps in Zaire. More than half a million more flooded into Tanzania. Another quarter of a million chose Burundi. These are all countries that have difficulty caring for their own people and they were immediately overwhelmed" (Stephen Kinzer)

Farmers, businessmen and teachers...

As we drove down a track towards the UN main compound I noticed that the crowds were moving to and from a lake. They carried water in buckets, pails, plastic bags, anything that could be filled.

Until a few weeks ago these people had lived and worked in Rwanda. They were farmers, businessmen, teachers -an entire society transplanted on to Tanzanian soil...

The people at Benaco were in a state of wretched poverty dependent on food hand-outs from the international community. They lived in plastic huts without sanitation, having lost their homes and land. Yet, as I moved among them, witnessing the squalor and desolation, I could not shut out the memory of Nyarabuye or the knowledge that among these huge crowds were thousands of people who had taken part in the genocide."

From Seasons of Blood. A Rwandan Journey. by Fergal Keane

Fleeing from more than revenge

Two years later those families returned from the refugee camps to their plots of land still bearing their collective guilt. Their sense of shame is haunted today by the dread of suspicion, punishment, and revenge, and it mingles with the Tutsis’ traumatic anguish and infects the atmosphere, aptly described by Sylvie Umubyeyi: “There are those who fear the very hills where they should be working on their lands. There are those who fear encountering Hutus on the road. There are Hutus who saved Tutsis but who no longer dare go home to their villages, for fear that no one will believe them. There are people who fear visitors, or the night. There are innocent faces that frighten others and fear they are frightening others, as if they were criminals. There is the fear of threats, the panic of memories.”

After a genocide, the anguish and dread have an agonizing persistence. The silence on the Rwandan hills is indescribable and cannot be compared with the usual mutism in the aftermath of war. Perhaps Cambodia offers a recent parallel. Tutsi survivors manage to surmount this silence only among themselves. But within the community of killers, innocent or guilty, each person plays the role of either a mute or an amnesiac.

From A time for machetes. The killers speak. by Jean Hatzfeld

< previous page | next page >

In this section

STARTING A GENOCIDE

Whose idea was it?

How did it start?

The foreigners are leaving

Hate radio

DETAILS

Roadblocks

The little things

INSIGHT

A simple plan

This new job

A strangeness of mind

Personalities

A good man

FOCUS ON THE BUGESERA

The Bugesera

Ntarama church massacre

A day in the marshes

MZUNGUS

The role of the west

Two French missionaries

A journalist's story

THE END OF THE GENOCIDE

The refugee crisis

A country with nobody home

Whose idea was it?

How did it start?

The foreigners are leaving

Hate radio

DETAILS

Roadblocks

The little things

INSIGHT

A simple plan

This new job

A strangeness of mind

Personalities

A good man

FOCUS ON THE BUGESERA

The Bugesera

Ntarama church massacre

A day in the marshes

MZUNGUS

The role of the west

Two French missionaries

A journalist's story

THE END OF THE GENOCIDE

The refugee crisis

A country with nobody home